Edward Heath

| The Right Honourable Sir Edward Heath KG MBE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In office 19 June 1970 – 4 March 1974 |

|

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

|---|---|

| Preceded by | Harold Wilson |

| Succeeded by | Harold Wilson |

|

Leader of the Opposition

|

|

| In office 4 March 1974 – 11 February 1975 |

|

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Prime Minister | Harold Wilson |

| Preceded by | Harold Wilson |

| Succeeded by | Margaret Thatcher |

| In office 28 July 1965 – 19 June 1970 |

|

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Prime Minister | Harold Wilson |

| Preceded by | Sir Alec Douglas-Home |

| Succeeded by | Harold Wilson |

|

Secretary of State for Industry, Trade and Regional Development, and President of the Board of Trade

|

|

| In office 20 October 1963 – 16 October 1964 |

|

| Prime Minister | Sir Alec Douglas-Home |

| Preceded by | Fred Erroll |

| Succeeded by | Douglas Jay |

|

Minister of Labour

|

|

| In office 14 October 1959 – 27 July 1960 |

|

| Prime Minister | Harold Macmillan |

| Preceded by | Iain MacLeod |

| Succeeded by | John Hare |

|

Lord Privy Seal

|

|

| In office 14 February 1960 – 18 October 1963 |

|

| Prime Minister | Harold Macmillan |

| Preceded by | Quintin Hogg |

| Succeeded by | Selwyn Lloyd |

|

Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasury

Chief Whip of the House of Commons |

|

| In office 7 April 1955 – 14 June 1959 |

|

| Prime Minister | Anthony Eden Harold Macmillan |

| Preceded by | Patrick Buchan-Hepburn |

| Succeeded by | Martin Redmayne |

|

Father of the House

|

|

| In office 9 April 1992 – 7 June 2001 |

|

| Prime Minister | John Major Tony Blair |

| Preceded by | Bernard Braine |

| Succeeded by | Tam Dalyell |

|

Member of Parliament

for Bexley |

|

| In office 23 February 1950 – 28 Feb 1974 |

|

| Preceded by | Ashley Bramall |

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

|

Member of Parliament

for Sidcup |

|

| In office 28 Feb 1974 – 9 June 1983 |

|

| Preceded by | New constituency |

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

|

Member of Parliament

for Old Bexley and Sidcup |

|

| In office 9 June 1983 – 7 June 2001 |

|

| Preceded by | New constituency |

| Succeeded by | Derek Conway |

|

|

|

| Born | 9 July 1916 Broadstairs, Kent United Kingdom |

| Died | 17 July 2005 (aged 89) Salisbury, Wiltshire United Kingdom |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Alma mater | Balliol College, Oxford |

| Profession | Journalist/ civil servant |

| Religion | Anglican |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Service/branch | British Army • Royal Artillery |

| Rank | Lieutenant Colonel |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | |

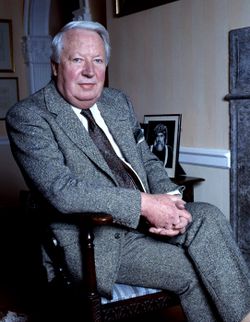

Sir Edward Richard George "Ted" Heath, KG, MBE (9 July 1916 – 17 July 2005) was a British politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1970–1974) and as leader of the Conservative Party (1965–1975). He was a Member of Parliament (MP) for Bexley (1950–1974), Sidcup (1974–1983) and Old Bexley and Sidcup (1983–2001).

Born in modest circumstances in 1916, in Broadstairs, England, Heath went on to study at Balliol College, Oxford. In 1938, Heath went to Spain to witness the ongoing Civil War and then served in the British Army during the Second World War.

Heath served as Chief Whip during the Suez Crisis of 1956, but formally became a cabinet member under Harold Macmillan as Minister of Labour (1959–1960), before leading the unsuccessful negotiations to join the European Economic Community in 1962-3. In 1965, Heath defeated Enoch Powell and Reginald Maudling for leadership of the Conservative Party. He lost the 1966 General Election to incumbent Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson, but won the 1970 Election and became Prime Minister.

Almost immediately, Heath applied for Britain to enter the European Economic Community (now the European Union) and was successful, although this decision upset many Conservative Party members, creating divisions that would last for over thirty years. Heath oversaw the completion of the decimalisation of British coinage in 1971, and the reorganisation of the English counties.

Heath's ministry saw the worst period of the Northern Ireland Troubles: the imposition of Direct British Rule, Internment and the Bloody Sunday shootings of 1972. In 1971, Heath sent a Secret Intelligence Service officer, Frank Steele to begin negotiations with the Provisional Irish Republican Army. An attempt to set up a new power-sharing government (Sunningdale) was unsuccessful.

Heath angered trade unions by bringing in an Industrial Relations Act and attempting to bring in a prices and income policy. In 1973, a miner's strike caused Heath to implement the Three-Day Week to conserve electricity. With the slogan 'Who Governs Britain', Heath called for an election in February 1974 which resulted in a hung parliament. After unsuccessful coalition talks between Heath and Liberal leader Jeremy Thorpe, Heath resigned as Prime Minister to be succeeded by Harold Wilson. Another election was held in October of that year and the Labour Party won by a small majority.

Heath was defeated by former Education and Science Secretary Margaret Thatcher in the 1975 Conservative Party Leadership contest. Subsequently, Heath returned to the backbenches, from whence he was an active critic of Thatcher's government. He was a key member in the Brandt Commission into North/South problems (1977–80). He retired at the 2001 General Election. He died in 2005 from pneumonia.

Heath was a world-class yachtsman and a musician of near-professional standard. He was also one of only four British Prime Ministers never to have married.

Early life

Edward Heath (known as "Teddy" as a young man) was born the son of a carpenter and a maid from Broadstairs, Kent. His father was later a successful small businessman. He was educated at Chatham House Grammar School in Ramsgate and in 1935 with the aid of a county scholarship he went up to study at Balliol College, Oxford. A talented musician, he won the college's Organ scholarship in his first term (he had previously tried for the organ scholarships at St Catharine's College, Cambridge, and Keble College, Oxford) which enabled him to stay at the University for a fourth year; he eventually graduated with a Second Class Honours BA in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics in 1939. In later life Heath's peculiar accent – with its "strangulated" vowel sounds – was satirised by the Monty Python's Flying Circus in the audio sketch "Teach Yourself Heath" (originally recorded for their 1972 LP Monty Python's Previous Record but not released at the time).[1] Heath's biographer John Campbell speculates that his speech, unlike that of his father and younger brother, who both spoke with Kent accents, must have undergone "drastic alteration on encountering Oxford".

While at university Heath became active in Conservative politics. However, on the key political issue of the day, foreign policy, he opposed the Conservative-dominated government of the day ever more openly. His first Paper Speech (i.e. a major speech listed on the order paper along with the visiting guest speakers) at the Oxford Union, in Michaelmas 1936, was in opposition to the appeasement of Germany by returning her colonies, confiscated after the First World War. In June 1937 he was elected President of the Oxford University Conservative Association as a pro-Spanish-Republican candidate, in opposition to the pro-Franco John Stokes (later a Conservative MP). In 1937-8 he was also chairman of the national Federation of University Conservative Associations, and in the same year (his third at University) he was Secretary then Librarian of the Oxford Union. At the end of the year, however, he was defeated for the Presidency of the Oxford Union by another Balliol candidate, Alan Wood, on the issue of whether the Chamberlain government should give way to a left-wing Popular Front. On this occasion Heath supported the government.

In his final year Heath was President of Balliol College Junior Common Room, an office held in subsequent years by his near-contemporaries Denis Healey and Roy Jenkins, and as such was invited to support the Master of Balliol Alexander Lindsay, who stood as an anti-appeasement 'Independent Progressive' candidate against the official Conservative candidate, Quintin Hogg, in the Oxford by-election, 1938. Heath, who had himself applied to be the Conservative candidate for the by-election,[2] accused the government in an October Union Debate of "turning all four cheeks" to Hitler, and was elected as President of the Oxford Union in November 1938, sponsored by Balliol, after winning the Presidential Debate that "This House has No Confidence in the National Government as presently constituted". He was thus President in Hilary Term 1939; the visiting Leo Amery described him in his diaries as "a pleasant youth".

As an undergraduate, Heath travelled widely in Europe. His opposition to appeasement was nourished by his witnessing first-hand a Nuremberg Rally in 1937, where he met top Nazis Hermann Göring, Joseph Goebbels and Heinrich Himmler at an SS cocktail party. He later described Himmler as "the most evil man I have ever met".[3] In 1938 he visited Barcelona, then under attack from Spanish Nationalist forces during the Spanish Civil War. In the summer of 1939 he again travelled across Germany, returning to England just before the declaration of war.

World War II

Heath spent the winter of 1939–40 on a debating tour of the United States before being called up, and early in 1941 was commissioned in the Royal Artillery. During World War II he initially served with heavy anti-aircraft guns around Liverpool (which suffered heavy German bombing in May 1941) and by early 1942 was regimental adjutant, with the rank of Captain. Later, now a Major commanding a battery of his own, he provided artillery support in the North-West Europe Campaign of 1944-1945.

He later remarked that, although he did not personally kill anybody, as the British forces advanced he saw the devastation caused by his unit's artillery bombardments. In September 1945 he commanded a firing squad to execute a Polish soldier convicted of rape and murder, a fact that he did not reveal until his memoirs were published in 1998. After demobilisation as a Lieutenant-colonel in August 1946 Heath joined the Honourable Artillery Company, in which he remained active throughout the 1950s, rising to Commanding officer of the Second Battalion; a portrait of him in full dress uniform still hangs in the HAC's Long Room. In April 1971, as Prime Minister, he wore his lieutenant-colonel's insignia to inspect troops.

Post war

Before the war Heath had won a scholarship to Gray's Inn and had begun making preparations for a career at the Bar, but after the war he instead passed top into the Civil Service. He then became a civil servant in the Ministry of Civil Aviation (he was disappointed not to be posted to the Treasury, but declined an offer to join the Foreign Office, fearing that foreign postings might prevent him from entering politics).[4] He resigned in November 1947 after his adoption as the prospective parliamentary candidate for Bexley.

After working as Editor of the Church Times from 1948 to 1949, Heath worked as a management trainee at the merchant bankers Brown, Shipley & Co. until his election as Member of Parliament (MP) for Bexley in the February 1950 general election. In the election he defeated an old contemporary from the Oxford Union, Ashley Bramall, with a majority of 133 votes.

Member of Parliament

Heath made his maiden speech in the House of Commons on 26 June 1950, in which he appealed to the Labour Government to participate in the Schuman Plan. As MP for Bexley, he gave enthusiastic speeches in support of the young, unknown candidate for neighbouring Dartford, Margaret Roberts, soon to become Margaret Thatcher.

In February 1951, Heath was appointed as an Opposition Whip by Winston Churchill. He remained in the Whip's Office after the Conservatives won the 1951 general election, rising rapidly to Joint Deputy Chief Whip, Deputy Chief Whip and, in December 1955, Government Chief Whip under Anthony Eden. Because of the convention that Whips do not speak in Parliament, Heath managed to keep out of the controversy over the Suez Crisis. On the announcement of Eden's resignation, Heath submitted a report on the opinions of the Conservative MPs regarding Eden's possible successors. This report favoured Harold Macmillan and was instrumental in eventually securing Macmillan the premiership in January 1957. Macmillan later appointed Heath Minister of Labour after the successful October 1959 election.

In 1960 Macmillan appointed Heath Lord Privy Seal with responsibility for the negotiations to secure the UK's first attempt to join the Common Market (as the European Community was then called). After extensive negotiations, involving detailed agreements about the UK's agricultural trade with Commonwealth countries such as New Zealand, British entry was vetoed by the French President, Charles de Gaulle, at a press conference in January 1963. After this setback, a major humiliation for Macmillan's foreign policy, Heath was not a contender for the party leadership on Macmillan's retirement in October 1963. Under Prime Minister Sir Alec Douglas-Home he was President of the Board of Trade and Secretary of State for Industry, Trade and Regional Development, and oversaw the abolition of retail price controls.

Leadership bid

After the Conservative Party lost the general election of 1964, the defeated Home changed the party leadership rules to allow for an MP ballot vote, and then resigned. The following year, Heath – who was Shadow Chancellor at the time, and had recently won favourable publicity for leading the fight against Labour's Finance Bill – unexpectedly won the party's leadership contest, gaining 150 votes to Reginald Maudling's 133 and Enoch Powell's 15.[5] Heath became the Tories' youngest leader and retained office after the party's defeat in the general election of 1966.

Leader of the Opposition

Heath sacked Enoch Powell from the Shadow Cabinet in April 1968, shortly after Powell made his inflammatory "Rivers of Blood" speech which criticised Commonwealth immigration to the United Kingdom.

Heath never spoke to Powell again. Powell had not notified Conservative Central Office of his intention to deliver the speech, and this was put forward as one reason for his dismissal.

When Powell died on 8 February 1998, Heath was asked for his reaction, but he simply told the media: "I won't be making a statement."

Prime minister

With another general election approaching in 1970 a Conservative policy document emerged from the Selsdon Park Hotel that, according to some historians,[6] offered monetarist and free-market oriented policies as solutions to the country's unemployment and inflation problems. Heath stated that the Selsdon weekend only reaffirmed policies that had actually been evolving since he became leader of the Conservative Party. The prime minister, Harold Wilson, thought the document a vote-loser and dubbed it Selsdon Man in order to portray it as reactionary. But Heath's Conservative Party won the general election of 1970.

The new cabinet included Margaret Thatcher (Education and Science), William Whitelaw (Leader of the House of Commons) and the former prime minister Sir Alec Douglas-Home (Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs).

Heath's time in office was as difficult as that of all British prime ministers in the 1970s. The government suffered an early blow with the death of Chancellor of the Exchequer Iain Macleod on 20 July 1970; his replacement was Anthony Barber. Heath's planned economic policy changes (including a significant shift from direct to indirect taxation) remained largely unimplemented: the Selsdon policy document was more or less abandoned as unemployment increased considerably by 1972 (the so-called "U-Turn"). From this point the economy was inflated in an attempt to bring unemployment down, the so-called "Barber Boom".

Heath attempted to rein in the increasingly militant trade union movement, which had so far managed to stop attempts to curb their power by legal means. His Industrial Relations Act set up a special court under the judge Lord Donaldson, whose imprisonment of striking dockworkers was a public relations disaster that the Thatcher Government of the 1980s would take pains to avoid repeating (relying instead on confiscating the assets of unions found to have broken new anti-strike laws). Heath's attempt to confront trade union power resulted in a political battle, hobbled as the government was by inflation and high unemployment. Especially damaging to the government's credibility were the two miners' strikes of 1972 and 1974, the latter of which resulted in much of the country's industry working a Three-Day Week in an attempt to conserve energy. The National Union of Mineworkers won its case but the energy shortages and the resulting breakdown of domestic consensus contributed to the eventual downfall of his government.

Heath's government did not curtail welfare spending, though at one point the squeeze in the education budget resulted in Margaret Thatcher, then Secretary of State for Education and Science, acting on the late Iain Macleod's wishes, ending the provision of free school milk from 8 to 11 year olds (the preceding Labour Government having removed it from secondary schools three years before) for which the tabloid press christened her "Thatcher the Milk Snatcher".[7] She did however succeed in blocking Macleod's other posthumous Education policy of abolishing the Open University recently founded by the preceding Labour Government.[8]

Heath's government's 1972 Local Government Act changed the boundaries of England's counties and created "Metropolitan Counties" around the major cities (e.g. Merseyside around Liverpool): this caused significant public anger. However, Heath did not divide England into regions, choosing instead to await the report of the Crowther Commission on the constitution; the ten Government Office Regions were eventually set up by the Major government in 1994.

The decimalisation of British coinage, begun under the previous Labour Government, was completed eight months after he came to power. He established the Central Policy Review Staff in February 1971.[9]

Foreign policy

Heath took the United Kingdom into the European Community in 1973. In October 1973 he placed a British arms embargo on all combatants in the Arab-Israeli Yom Kippur war that mainly affected the Israelis in obtaining spares for their Centurion tanks. He favoured links with the People's Republic of China, visiting Mao Zedong in Beijing in 1974 and 1975 and remaining an honoured guest in China on frequent visits thereafter and forming a close relationship with Mao's successor Deng Xiaoping. Heath also maintained a good relationship with US President Richard Nixon and figures in the Iraqi Baath party.

Northern Ireland

Heath governed during a bloody period in the history of the Northern Ireland Troubles. On Bloody Sunday in 1972, 14 unarmed men were killed by British soldiers during an illegal march in Derry. (In 2003, he gave evidence to the Saville Inquiry and stated that he had never sanctioned unlawful lethal force in Northern Ireland). Although the success of the Northern Ireland peace process is now frequently attributed to others, it was in fact Heath, who in early 1971 sent in a Secret Intelligence Service officer, Frank Steele, to talk to the Provisional Irish Republican Army and find out what common ground there was for negotiations. Steele had carried out secret talks with Jomo Kenyatta ahead of the British withdrawal from Kenya.[10] In July 1972, Heath permitted his Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, William Whitelaw, to hold unofficial talks in London with a Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) delegation by Seán Mac Stiofáin. In the aftermath of these unsuccessful talks, the Heath government pushed for a peaceful settlement with the democratic political parties.

The 1973 Sunningdale Agreement, which proposed a power-sharing deal, was strongly repudiated by many Unionists and the Ulster Unionist Party who withdrew its MPs at Westminster from the Conservative whip, The proposal was finally brought down by the loyalist Ulster Workers Council strike in 1974. However, much of what was contained in the Sunningdale Agreement found its way into the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, which was once described memorably by the then deputy leader of the SDLP, Seamus Mallon, as "Sunningdale for slow learners" , a reference to the failed power-sharing deal of 1973

Heath was targeted by the IRA for introducing internment in Northern Ireland. In December 1974, the Balcombe Street ASU threw a bomb onto the first-floor balcony of his home in Wilton Street, Belgravia where it exploded. Heath had been conducting a Christmas Carol concert in his constituency at Broadstairs and arrived home 10 minutes after the bomb exploded. No one was injured in the attack, but a landscape portrait painted by Winston Churchill — given to Heath as a present — was damaged.[11]

Fall from power

1974 general elections

Heath tried to bolster his government by calling a general election for 28 February 1974, using the election slogan "Who governs Britain?". The result of the election was inconclusive with no party gaining an overall majority in the House of Commons; the Tories had the most votes but Labour had slightly more seats. Heath began negotiations with Jeremy Thorpe, leader of the Liberal Party but, when these failed, he resigned as Prime Minister on 4 March 1974, and was replaced by Wilson's minority Labour government, eventually confirmed, though with a tiny majority, in a second election in October of the same year.

The Centre for Policy Studies, a Conservative group closely involved with the 1970 Selsdon document, began to formulate a new monetarist and free-market policy, initially led by Sir Keith Joseph. Although Margaret Thatcher was associated with the CPS she was initially seen as a potential moderate go-between by Heath's lieutenant James Prior.

The rise of Thatcher

Heath came to be seen as a liability by many Conservative MPs, party activists and newspaper editors. He resolved to remain Conservative leader, even after two general election defeats in one year, and at first it appeared that by calling on the loyalty of his front bench colleagues he might prevail. At the time the Conservative leadership rules allowed for an election to fill a vacancy but contained no provision for a sitting leader to either seek a fresh mandate or be challenged. In the weeks following the second election defeat, Heath came under tremendous pressure to concede a review of the rules and agreed to establish a commission to propose changes and to seek re-election. There was no clear challenger after Enoch Powell had left the party and Keith Joseph had ruled himself out after controversial statements implying that the working classes should be encouraged to use more birth control. However Joseph's close friend and ally Margaret Thatcher, who believed an adherent to CPS philosophy should stand, joined the leadership contest in his place alongside the outsider Hugh Fraser.[6] Aided by Airey Neave's campaigning amongst back-bench MPs – whose earlier approach to William Whitelaw had been rebuffed out of loyalty to Heath – she emerged as the only serious challenger.[6]

The new rules permitted new candidates to enter the ballot in a second round of voting should the first be inconclusive, so Thatcher's challenge was considered by some to be that of a stalking horse. Neave deliberately understated Thatcher's support in order to attract wavering votes from MPs who were keen to see Heath replaced even though they did not necessarily want Thatcher to replace him.[12][13]

On 4 February 1975, Thatcher defeated Heath in the first ballot by 130 votes to 119, with Fraser coming in a distant third with 16 votes. This was not a big enough margin to give Thatcher the 15% majority necessary to win on the first ballot, but having finished in second place Heath immediately resigned and did not contest the next ballot. His favoured candidate, William Whitelaw, lost to Thatcher in the second vote one week later (Thatcher 146, Whitelaw 79, Howe 19, Prior 19, Peyton 11).

When Thatcher visited Heath the day after her election as leader, accounts differ as to whether or not she offered him a place in her shadow cabinet – by some accounts she was detained for coffee by a colleague so that the waiting press would not realise how brief the meeting had been.[14] Heath stated that he had already informed her that he did not want a place and that the purpose of her visit was to seek his advice as to how to handle the press. Nonetheless after the 1979 general election he was offered, and declined, the post of British Ambassador to the United States.

Later career

Heath for many years persisted in criticism of the party's new ideological direction. At the time of his defeat he was still popular with rank and file Conservative members and was warmly applauded at the 1975 Party Conference. He continued as a central figure on the left of the party and, at the 1981 Conservative Party conference, openly criticised the government's economic policies – namely monetarism, which had seen inflation cut from 27% in 1979 to 4% by 1983, but had seen unemployment double from around 1,500,000 to a postwar high of more than 3,000,000 during that time.[15]

He campaigned in the 1975 referendum in which Britain voted to remain part of the EEC and remained active on the international stage, serving on the Brandt Commission investigation into developmental issues, particularly on North-South projects (Brandt Report). In 1990 he flew to Baghdad to attempt to negotiate the release of British aircraft passengers taken hostage when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. After Black Wednesday in 1992 he stated in the House of Commons that government should build a fund of reserves to counter currency speculators.

In the 1960s Heath had lived at a flat in the Albany, off Piccadilly; at the unexpected end of his premiership he took the flat of a Conservative MP Tim Kitson for some months. In February 1985 Heath moved to Salisbury, where he resided until his death over 20 years later. In 1987 he was nominated in the election for the Chancellorship of the University of Oxford but came third, behind Roy Jenkins and Lord Blake.

Heath continued to serve as a back bench MP for the London constituency of Old Bexley and Sidcup and was, from 1992, the longest-serving MP ("Father of the House") and the oldest British MP. As Father of the House he oversaw the election of two Speakers of the Commons, Betty Boothroyd and Michael Martin. Heath was created a Knight of the Garter on 23 April 1992.[16] He retired from Parliament before the 2001 general election.

Parliament broke with precedent by commissioning a bust of Heath while he was still alive.[17] The 1993 bronze work, by Martin Jennings, was moved to the Members' Lobby in 2002.

Death

In August 2003, at the age of 87, Heath suffered a pulmonary embolism while on holiday in Salzburg, Austria. He never fully recovered, and owing to his declining health and mobility made very few public appearances in the final two years of his life. His last ever public appearance was at the unveiling of a set of gates to Winston Churchill at St Paul's Cathedral on 30 November 2004.

Heath paid tribute to James Callaghan when he died on 26 March 2005 saying that "James Callaghan was a major fixture in the political life of this country during his long and varied career. When in opposition he never hesitated to put firmly his party's case. When in office he took a smoother approach towards his supporters and opponents alike. Although he left the House of Commons in 1987 he continued to follow political life and it was always a pleasure to meet with him. We have lost a major figure from our political landscape".[18]

This was his last public statement. Heath died from pneumonia on the evening of 17 July 2005, at the age of 89. He was cremated on 25 July 2005 at a funeral service attended by fifteen hundred people. The day after his death the BBC Parliament channel showed the BBC results coverage of the 1970 election. A memorial service was held for Heath in Westminster Abbey on 8 November 2005 which was attended by two thousand people. Three days later his ashes were interred in Salisbury Cathedral. In a tribute to him, the then Prime Minister Tony Blair stated "He was a man of great integrity and beliefs he held firmly from which he never wavered".[19]

Arundells

In January 2006, it was announced that Heath had left £5 million in his will, most of it to a charitable foundation to conserve his eighteenth-century house, Arundells, opposite Salisbury Cathedral as a museum to his career. The house was open to the public for guided tours from March to September, and preserved a large collection of personal effects as well as Heath's personal library, photo collections and paintings by Winston Churchill.[20] The Trustees of his will are approaching the Charity Commission for permission to sell the house and contents after it closes to the public in October 2010 as there is a shortfall in the charity's income, despite rising visitor numbers.

In his will Heath, who had had no descendants, left only two legacies: £20,000 to his brother's widow, and £2500 to his housekeeper.[21]

Personal life

Yachting

Heath was a keen yachtsman. He bought his first yacht Morning Cloud in 1969 and won the Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race that year. He captained Britain's winning team for the Admiral's Cup in 1971 — while Prime Minister — and also captained the team in the 1979 Fastnet race. He was a member of the Sailing Club in his home town, Broadstairs. Heath's hobby is referred to in the 2008 film The Bank Job where it is said that the Prime Minister himself may meet with the bank robbers "if you can drag him off his yacht".[22]

Conductor

Heath also maintained an interest in orchestral music as an organist and conductor, famously installing a Steinway grand in 10 Downing Street — bought with his £450 Charlemagne Prize money, awarded for his unsuccessful efforts to bring Britain into the EEC in 1963, and chosen on the advice of his friend, the pianist Moura Lympany — and conducting Christmas carol concerts in Broadstairs every year from his teens until old age. Heath often played the organ for services at Holy Trinity Church Brompton in his early years.

Heath conducted the London Symphony Orchestra, notably at a gala concert at the Royal Festival Hall in November 1971, at which he conducted Sir Edward Elgar's overture Cockaigne (In London Town). He also conducted the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic and the English Chamber Orchestra, as well as orchestras in Germany and the United States. Heath received honorary degrees from the Royal College of Music and Royal College of Organists. During his premiership, Heath invited musician friends, such as Isaac Stern, Yehudi Menuhin, Clifford Curzon and the Amadeus Quartet, to perform either at Chequers or Downing Street.

In 1988, Heath recorded Beethoven's Triple Concerto, Op. 56 and Boccherini's Cello Concerto in G major, G480.

Performing arts

Heath enjoyed the performing arts as a whole. In particular, he gave a great deal of support to performing arts causes in his constituency and was known to be proud of the fact that his constituency boasted two of the country's leading performing arts schools. Rose Bruford College and Bird College are both situated in Sidcup, and a purpose built facility for the latter was officially opened by Heath in 1979.

Heath also wrote a book called The Joy of Christmas: A Collection of Carols, published in 1978 by Oxford University Press and including the music and lyrics to a wide variety of Christmas Carols each accompanied by a reproduction of a piece of religious art and a short introduction by Heath.

Sport

Unusually for someone living in the south of England, Heath was a supporter of the Lancashire based football club Burnley.[23]

Author

He wrote three non-political books, Sailing, Music, and Travels, and an autobiography, The Course of My Life (1998). The latter took 14 years to produce; Heath's obituary in the Daily Telegraph alleged that he never paid many of the ghost-writers.

Sexuality

Heath was a lifelong bachelor. Heath's interest in music kept him on friendly terms with a number of female musicians including Moura Lympany, and he always had the company of women when social circumstances required. Lympany had thought he would marry her, but when asked about the most intimate thing he had done, replied, "He put his arm around my shoulder."[24]

John Campbell, who published a biography of Heath in 1993, devoted four pages to a discussion of the evidence concerning Heath's sexuality. Whilst acknowledging that Heath was often assumed by the public to be gay, not least because it is "nowadays ... whispered of any bachelor" he found "no positive evidence" that this was actually so "except for the faintest unsubstantiated rumour" (the footnote refers to a mention of a "disturbing incident" at the beginning of World War II in a 1972 biography by Andrew Roth).[25] Campbell also pointed out that Heath was at least as likely to be a repressed heterosexual (given his awkwardness with women) although he thought it unlikely that he was "asexual" given how "unrelaxed" he was about sexual matters, and concluded that the fact of Heath's sublimation of his sexuality was more important than what his original inclinations had been.

Heath had been expected to marry childhood friend Kay Raven, who reportedly tired of waiting and married an RAF officer whom she met on holiday in 1950. In a terse four-sentence paragraph of his memoirs, Heath claimed that he had been too busy establishing a career after the war and had "perhaps ... taken too much for granted". In a 1998 TV interview with Michael Cockerell, Heath admitted that he had kept her photograph in his flat for many years afterwards.

After Heath's death, Conservative London Assembly member Brian Coleman wrote for New Statesman in 2007 on the issue of outing, "The late Ted Heath managed to obtain the highest office of state after he was supposedly advised to cease his cottaging activities in the 1950s when he became a privy councillor" suggesting that Heath was gay.[26][27] The claim was denied by MP Sir Peter Tapsell and Heath's friend and MP Derek Conway stated that "if there was some secret, I'm sure it would be out by now".[28][29]

Titles from birth

- Edward Heath, Esq (9 July 1916–1992)

- Lieutenant Colonel Edward Heath (1945)

- Lieutenant Colonel Edward Heath, MBE (1946)

- Edward Heath, Esq, MBE (?-23 February 1950)

- Edward Heath, Esq, MBE, MP (23 February 1950–1955)

- The Right Honourable Edward Heath, MBE, MP (1955–24 April 1992)

- The Right Honourable Sir Edward Heath, KG, MBE, MP (24 April 1992–7 June 2001)

- The Right Honourable Sir Edward Heath, KG, MBE (7 June 2001– 17 July 2005)

Nicknames

Heath was persistently referred to as "The Grocer", or "Grocer Heath" by magazine Private Eye. The nickname, based upon the 1967 hit song "Excerpt From A Teenage Opera", was used periodically, but became a permanent fixture in the magazine after he fought the 1970 General Election on a promise to reduce the price of groceries.

Edward Heath's Government (June 1970 – March 1974)

- Prime Minister: Edward Heath

- Lord Chancellor: Lord Hailsham of St Marylebone

- Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Commons: William Whitelaw

- Lord Privy Seal and Leader of the House of Lords: Lord Jellicoe

- Chancellor of the Exchequer: Iain Macleod

- Foreign Secretary: Sir Alec Douglas-Home

- Home Secretary: Reginald Maudling

- Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food: James Prior

- Secretary of State for Defence: Lord Carrington

- Secretary of State for Education and Science: Margaret Thatcher

- Secretary of State for Employment: Robert Carr

- Minister of Housing and Local Government: Peter Walker

- Secretary of State for Health and Social Security: Keith Joseph

- Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster: Anthony Barber

- Secretary of State for Scotland: Gordon Campbell

- Secretary of State for Technology: Geoffrey Rippon

- President of the Board of Trade: Michael Noble

- Secretary of State for Wales: Peter Thomas

Changes

- July 1970 — Iain Macleod dies, and is succeeded as Chancellor by Anthony Barber. Geoffrey Rippon succeeds Barber as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. John Davies succeeds Rippon as Secretary for Technology.

- October 1970 — The Ministry of Technology and the Board of Trade are merged to become the Department of Trade and Industry. John Davies becomes Secretary of State for Trade and Industry. Michael Noble leaves the cabinet. The Ministry of Housing and Local Government is succeeded by the new department of the Environment which was headed by Peter Walker.

- March 1972 — Robert Carr succeeds William Whitelaw as Lord President and Leader of the House of Commons. Maurice Macmillan succeeds Carr as Secretary for Employment. Whitelaw becomes Secretary of State for Northern Ireland.

- July 1972 — Robert Carr succeeds Reginald Maudling as Home Secretary. James Prior succeeds Robert Carr as Lord President and Leader of the House of Commons. Joseph Godber succeeds Prior as Secretary for Agriculture.

- November 1972 — Geoffrey Rippon succeeds Peter Walker as Secretary for the Environment. John Davies succeeds Rippon as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. Peter Walker succeeds Davies as Secretary for Trade and Industry. Geoffrey Howe becomes Minister for Trade and Consumer Affairs with a seat in the cabinet.

- June 1973 — Lord Windlesham succeeds Lord Jellicoe as Lord Privy Seal and Leader of the House of Lords.

- December 1973 — William Whitelaw succeeds Maurice Macmillan as Secretary for Employment. Francis Pym succeeds Whitelaw as Secretary for Northern Ireland. Macmillan becomes Paymaster-General.

- January 1974 — Ian Gilmour succeeds Lord Carrington as Secretary for Defence; Lord Carrington becomes Secretary of State for Energy.

Honorary degrees

- University of Calgary 7 June 1991 (LLD)[30][31]

- University of Wales (LLD) 1998[32]

- University of Greenwich (LLD) 18 July 2001[33]

Arms

|

||||||||||

References

Books:

- Heath, Edward. Sailing: A Course of My Life. London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1975.

- Heath, Edward. Music: A Joy for Life. London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1976.

- Heath, Edward. Travels: People and Places in My Life. London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1977.

- Heath, Edward. The Course of My Life. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1998.

Biographies:

- Ball, Stuart & Seldon, Anthony (editors). The Heath Government: 1970–1974: A Reappraisal. London: Longman, 1996.

- Campbell, John. Edward Heath: A Biography. London: Jonathan Cape, 1993.

- Holmes, Martin. The Failure of the Heath Government. Basingstoke: Longman, 1997.

- Ziegler, Philip, Edward Heath, Harper Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-00724-740-0

Footnotes

- ↑ "Learn How To Speak Propah English – Ted Heath | Teach Yourself Heath". Youtube.com. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NZByWk6SPM0. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ Heath, Edward. The Course of My Life. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1998, p58

- ↑ "House of Commons Hansard Debates for 18 Jul 2005 (pt. 6)". 2005. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200506/cmhansrd/vo050718/debtext/50718-06.htm. Retrieved 30 Mar. 2009.

- ↑ Heath, Edward. The Course of My Life. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1998, p111

- ↑ "BBC ON THIS DAY – Heath is new Tory leader". BBC News. 27 July 1996. http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/july/27/newsid_2956000/2956082.stm. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Young, Hugo. One Of Us London: MacMillan, 1989

- ↑ Young, Hugo (1989) One Of Us London: Macmillan

- ↑ Young, Hugo (1989)

- ↑ Greenwood, John R.; Wilson, David Jack (1989). Public administration in Britain today. Routledge. p. 58. ISBN 9780044451952.

- ↑ Smith, Michael, The Spying Game, the Secret History of British Espionage, Politicos, London, pp378-382

- ↑ "History – The Year London Blew Up". Channel 4. http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/H/history/t-z/year02.html. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ Campbell, John The Grocer's Daughter

- ↑ Heath, Edward. The Course of My Life. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1998, p532

- ↑ Heath, Edward,"The Course of My Life", London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1998, P537

- ↑ "Economics Essays: UK Economy under Mrs Thatcher 1979-1984". Econ.economicshelp.org. http://econ.economicshelp.org/2007/03/uk-economy-under-mrs-thatcher-1979-1984.html. Retrieved 2010-08-17.

- ↑ Official announcement of knighthood for Heath – The London Gazette, issue 52903, 24 april 1992

- ↑ UK Parliament: Unveiling of a Statue of Baroness Thatcher in Members Lobby, House of Commons Commentators have noted how the statue of Margaret Thatcher appears to overshadow Heath's bust.

- ↑ "UK | Politics | 'Tough operator' remembered". BBC News. 26 March 2005. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/4385189.stm. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ "Edward Heath". Number10.gov.uk. http://www.number10.gov.uk/history-and-tour/prime-ministers-in-history/edward-heath. Retrieved 2010-08-17.

- ↑ http://www.arundells.org/ Arundells

- ↑ "Politics | Former PM Heath left £5m in will". BBC News. 20 January 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/4632094.stm. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ The Bank Job (2008) – Memorable quotes

- ↑ "Famous Football Fans". The-football-club.com. http://www.the-football-club.com/famous-football-fans.html. Retrieved 2010-08-17.

- ↑ The Guardian, 19 March 2001

- ↑ Grice, Andrew (25 April 2007). "Heath was told to stop gay sex activity, Tory claims". The Independent (London). http://news.independent.co.uk/uk/politics/article2483866.ece. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ Coleman, Brian (23 April 2007). "The closet is a lonely place". The New Statesman. http://www.newstatesman.com/200704230063. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ Jones, George (25 April 2007). "Heath warned about gay sex trysts". Daily Telegraph (London). http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2007/04/25/nheath25.xml. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ Bob Roberts (25 April 2007). "Hamps-Ted Heath". Daily Mirror. http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/topstories/tm_headline=hamps-ted-heath&method=full&objectid=18958668&siteid=89520-name_page.html. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ "PM Ted 'cruised for gay sex'". The Sun. 25 April 2007. http://www.thesun.co.uk/article/0,,2-2007190138,00.html. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ "CONTENTdm Collection : Browse". Contentdm.ucalgary.ca. http://contentdm.ucalgary.ca/cdm4/browse.php?CISOROOT=/archiveshd&CISOSTART=1,121. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ "Press release". W3.gre.ac.uk. 19 July 2001. http://w3.gre.ac.uk/pr/releasearchive/583.htm. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ Chesshyre, Hubert (1996). The Friends of St. George's & Descendants of the Knights of the Garter Annual Review 1995/96. VII. p. 289

External links

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Edward Heath

- Obituary in The Guardian

- Heath, Edward Chronology

- More about Edward Heath on the Downing Street website.

- Arundells, Sir Edward Heath's home

- [3] Charles Moore reviews 'Edward Heath' by Philip Ziegler (Harper Press).

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by William Wilkins |

Junior Lord of the Treasury 1951–1955 |

Succeeded by Edward Wakefield |

| Preceded by Patrick Buchan-Hepburn |

Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasury (Government Chief Whip) 1955–1959 |

Succeeded by Martin Redmayne |

| Preceded by Iain MacLeod |

Minister of Labour 1959–1960 |

Succeeded by John Hare |

| Preceded by The Viscount Hailsham |

Lord Privy Seal 1960–1963 |

Succeeded by Selwyn Lloyd |

| Preceded by Fred Erroll |

Secretary of State for Industry, Trade and Regional Development, and President of the Board of Trade 1963–1964 |

Succeeded by Douglas Jay |

| Preceded by Sir Alec Douglas-Home |

Leader of the Opposition 1965–1970 |

Succeeded by Harold Wilson |

| Preceded by Harold Wilson |

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom 19 June 1970 – 4 March 1974 |

|

| Leader of the Opposition 1974–1975 |

Succeeded by Margaret Thatcher |

|

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

| Preceded by Ashley Bramall |

Member of Parliament for Bexley 1950–1974 |

Constituency abolished |

| New constituency | Member of Parliament for Sidcup 1974–1983 |

|

| Member of Parliament for Old Bexley and Sidcup 1983–2001 |

Succeeded by Derek Conway |

|

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Sir Alec Douglas-Home |

Leader of the British Conservative Party 1965–1975 |

Succeeded by Margaret Thatcher |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by Bernard Braine |

Father of the House 1992–2001 |

Succeeded by Tam Dalyell |

| Preceded by Michael Foot |

Oldest sitting Member of Parliament 1992–2001 |

Succeeded by Piara Khabra |

| Preceded by James Callaghan |

Oldest UK Prime Minister still living 26 March 2005 – 17 July 2005 |

Succeeded by Margaret Thatcher |

|

|||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

|||||

.svg.png)